Editor’s note: This essay was written as part of ENGL 1100, a dual credit college composition class through JAHS and Columbus State Community College.

People walk through life every day making decisions they’re unaware are based on implicit biases. Subconscious biases secretly affect the decision-making process in much more impactful ways than most people think. Judgment and prejudice are two infamous words the vast majority of people try to avoid associating with themselves. As a society, we believe, in the majority of cases, that we aren’t biased and we have equal and fair opinions regarding different groups of people. The impact of bias in society is overwhelming whether the differences are racial, cultural, age, sex, conventional attractiveness, or more. However, an aspect of bias in society that’s commonly overlooked is within the courtroom. Are juries truly unbiased? Are judges truly unbiased? I believe the answer to this question is no, and that people’s subconscious biases play a pivotal role in their perception of people’s guilt. Due to this, I believe jurors and judges sentence people in certain groups more severely, and other groups more leniently.

Many people overlook bias in the courtroom, but in reality there is copious space for bias to drive court proceedings. Not only this, but the impact of bias on the well-being of people is detrimental and severe in this setting. Thus, it’s very important to address bias in the setting of a courtroom. While there are safeguards in place, such as the Eighth Amendment (protections against cruel and unusual punishment), and juror striking (the ability to remove jurors you believe may have sentence altering bias judging the case), The bias that creeps through the safeguards is still substantial; a few more years in prison based on a bias is monumental. Shawn C. Marsh, who has been studying courtroom bias for years, explains, “There have been numerous studies on the impartiality of judges. Some findings show that trial court judges ‘rely extensively on intuition, more than deliberative judging, in deciding matters before the bench.’ This provides more opportunities for the judges to apply their implicit biases to the matters at hand.” He then goes on to say these biases affect jurors and attorneys too (Marsh). All of this bias looming over justice begs the question of just how substantial the effects truly are. With all the discretion being given to these different members of the court deciding the future of people’s lives, it isn’t something to be taken lightly.

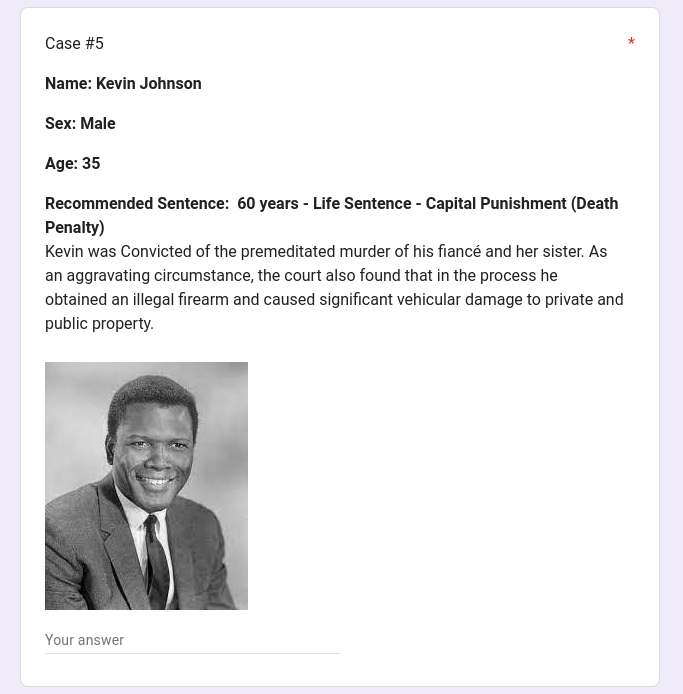

To help answer this question, I decided to conduct my own experiment – using the student body at Jonathan Alder – alongside my research. The variables I researched and tested revolved around specific kinds of subconscious biases: ageism, sexism, racial bias, beauty bias, and name bias. To do so, I created two tests, and had a total of 66 participants (33 taking test one, and 33 taking test two). On each test, there were ten questions. Each question had a picture of a person, along with their age, sex, name, “alleged crime,” and a typical sentencing range. The participants were asked to decide the sentences for each case that they deemed fitting. Each question on test one had a replica on test two where one variable changed, and each variable had two questions testing it exclusively. I then averaged the sentences and compared them (Kennedy). These results proved heavily in favor of my thesis, that bias has a major impact on sentencing, and as the different kinds of bias and their impact are explained my results will be looped in. . These results help prove that without a doubt bias plays a huge role in sentencing.

Ageism was one tested variable I found to have a mildly substantial impact on sentencing. To define ageism more specifically, “Ageism is when an individual is negatively discriminated against because of their age. Ageism can affect both young and older people” (National School of Healthcare Science, England). Age is a prominent quality of any person when it comes to making initial assumptions about them. It’s one of the first qualities people notice about the people they meet. Back to the courtroom, in my findings, the younger people were on average sentenced more severely: specifically 17.95% more severe (Kennedy). The United States Sentencing Commission agrees older convicts are sentenced more leniently. They base this conclusion on three factors: infirmity, life expectancy, and the risk of recidivism (reoffending). The three of these factors tend to cause people to feel pity toward comparatively older people; thus, the majority of people feel compelled to give them a lesser sentence.

The next question I had was gender bias. Would men or women be sentenced more leniently? Moreover, would social stigmas/norms play into the results? It’s undeniable that in our society there is a stigma around women’s bodies. All over the world, and from every background, women have been vocal about all the sexist preconceived notions applied to them. Whether it be talking about periods or choice of clothing women are practically shamed for talking about themselves and their bodies around other people. It was interesting to me that, in my experiment, when I fabricated a case with indecent exposure, where the independent variable was gender, the woman was given on average a 95.42% more severe sentence (Kennedy). However, in society there is generally also a stigma of women being weaker, so in the case where the crime was more physically entailed, the man was sentenced 49.15% more severely (Kennedy). These results perfectly align with social norms and stigmas, once again proving the overwhelming presence of subconscious bias. It also shows there may be a tie between social constructs and subconscious bias, and that the stems of bias may be more of a network; proving biases play off and enhance one another.

Next up on my docket was racial bias; which again I found to have an extremely monumental impact; Racial bias ended up being the most severe independent variable in regards to sentencing disparity. This is a bias that’s been very active in political conversations all over the world. It’s also one that has been tested many times before: “The Guilty/Not Guilty IAT asked study participants to group together photos of Black and White men with words representing the verdicts Guilty and Not Guilty, and measured their reaction times in milliseconds. The results of the study are concerning: study participants held strong implicit associations between Black men and guilty verdicts” (Levinson, Richardson, Young). When people in a study are unaware of what is being measured the results are typically striking. In my experiment, the non-white offenders were sentenced 213.71% more severely on average (Kennedy). With such an important and relevant bias it’s tragic to see such a high disparity between sentencing. In addition, in the results of one of the cases I created testing race, three people sentenced the white man to death, while eight sentenced the African American man to death. Which proves a quite upsetting reality regarding the strength of implicit biases revolving around race, and just how impactful and detrimental subconscious bias can be.

Beauty bias is one of the most prominent biases in society. While rarely explicitly mentioned, it carries some of the most weight in day-to-day implicit decision-making. While you may not realize it, beauty bias impacts numerous different aspects of your perception of people. To specify, “Beauty bias can exist if we find that we prefer people we perceive as beautiful and if we are making judgments based on appearances and are judging others harshly based on their appearance” (National School of Healthcare Science, England). These biases can prove very harsh in certain situations, and previous studies can corroborate that statement, “Professor Rachel Gordon from the University of Illinois in Chicago conducted some research into the connection between conventional physical attractiveness and the accumulation of social and human capital in young adults. One facet of the research indicated that conventionally ‘attractive’ people, both men and women, earn higher incomes, whereas ‘less attractive’ people earn lower incomes” (National School of Healthcare Science, England). While this is specifically looking at beauty bias in correlation to wages, I wanted to test if this also applied in the courtroom; to which the answer was a resounding yes. In my experiment, the conventionally “unattractive” people received on average 60.47% more severe sentences compared to their conventionally “attractive” counterparts (Kennedy). One scenario of which being so extreme that the average sentence for one of the conventionally “unattractive” people received on average more than twice as harsh sentencing. Which undeniably proves the prominence of yet another bias hampering the well being of those deemed “unattractive” in society.

A bias I was rather unaware of until the beginning of my research was name bias. Which once again was found to affect sentencing. The concept of which is fairly simple, “A name bias occurs when an individual is negatively discriminated against because of their name” (National School of Healthcare Science, England). While commonly overlooked this is another bias that’s been proven to be backseat driving many aspects of society. A notable example of this is a Harvard study, “white names receive 50% more call-backs for interviews than African American names. The Harvard Project Implicit study also found that replacing an ‘international’ name with an English name increased candidates’ chances of being hired” (National School of Healthcare Science, England). After reading some of this information I was eager to put this bias to test in the courtroom setting. To which the results were once again on par with the rest of the aspects of society. I used two last names very popular with the public for their relation to criminal activity. The results showed merely changing the names resulted in those with previous criminal association being sentenced 6.51% more harshly (Kennedy).

All of this information provides a pretty definitive answer to the question of just how significantly subconscious biases affect perceived guilt. Between age, sex, race, beauty, and name, the impact of implicit bias in the courtroom is palpable. Because their impact is vastly more severe and deep-rooted than it may initially appear, these sometimes fractional percent differences, while just numbers, have and will continue to represent years of unfair sentencing given to certain groups for things out of their control. Not to mention this all only covers five of the numerous kinds of bias that plague our society. So, in a final sentence to answer the question; people’s subconscious biases have a very significant impact on their perceived guilt of people, and certain groups of people are sentenced much more harshly than others. Jonathan Alder, It’s vital, not just in the courtroom setting, but in day-to-day life, to be aware of your implicit biases.

Works Cited

Kennedy, Ashton. Social Experiment Testing the Impact of Subconscious Bias on Court Sentencing. 20 Nov. 2023.

Levinson, Justin D. and Cai, Huajian and Young, Danielle, Guilty by Implicit Racial Bias: The Guilty/Not Guilty Implicit Association Test (September 10, 2009). Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1471567

Marsh, Shawn C. “Research Guides: Implicit Bias in the Law: In the Courts.” In the Courts – Implicit Bias in the Law – Research Guides at University of Connecticut School of Law, 16 Feb. 2021, libguides.law.uconn.edu/implicit/courts#:~:text=Attorneys%20and%20 Judges,-Attorney%20bias%20can&text=For%20example%2C%20they%20can%20choose,on%20the%20lives%20of%20defendants.

National School of Healthcare Science, England. “Understanding Different Types of Bias.” NHS Choices, NHS, 13 Oct. 2022, nshcs.hee.nhs.uk/about/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/ conscious-inclusion/understanding-different-types-of-bias/.

Sentencing Commission, US. “Older Offenders in the Federal System.” United States Sentencing Commission, 21 July 2022, www.ussc.gov/research/research-reports/older-offenders- federal-system. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.